Steve Jobs and the Rise and Fall of NeXT: Part 2

The conclusion of NeXT's story, from dropping its hardware division to being acquired by Apple, OSX, and beyond.

Note from Jonathan: This is the provisional final draft of the NeXT part 2 script. I will probably do at least one more editing pass over it before recording, but any changes should be minor. If I make any substantive changes in my final editing pass, I will update this article accordingly. I welcome any comments and constructive criticism, part of the reason this has taken so long to write is just how many threads make up this fascinating part of tech history and I want to make sure I do my best to do justice to them.

Welcome to another boring topic, and the long delayed conclusion to NeXT’s story. I made multiple attempts to get this story scripted, but I really struggled to find the right thread to follow. It would be fairly easy, even for someone as long-winded as I tend to be, to make this a ten minute video that basically boiled down to “NeXT floundered as a software only company for several years, and then Steve Jobs convinced Apple to buy the whole company, NextStep OS became the basis for Mac OS 10, and NeXT itself was never really spoken of again as Jobs and Apple began their long climb back to cultural domination.”

And in many ways this would be substantially accurate, NeXT’s direct story really does basically end with Apple’s purchase of it in late 1996. Steve Job’s favorite biographer, Walter Isaacson, gives NeXT very little space in his biography of Jobs, and the two primary books on NeXT itself, iFailed and Steve Jobs and the NeXT Big Thing, are really solely concerned with events prior to NeXT’s abandonment of its hardware side. iFailed basically stops right as NeXT’s hardware division was about to be sold to Canon at the end of 1993, and since Steve Jobs and the NeXT Big Thing was published in 1993, it only carries the story up to basically that same point as well.

And yet, there is so much more to the story. The rest of NeXT’s story is also the story of Apple’s rebirth, of Steve Job’s rehabilitation as a visionary CEO, and of the Macintosh operating system finally making the transition to a modern OS, after multiple high profile and expensive failures. It’s the story of an operating system that quietly underpins multiple types of devices today, ranging from mobile, to set-top boxes, and the technology that did so much to give us the modern computing world. It’s a complicated, convoluted, and complex story that I am going to try to do justice to, to the best of my ability.

But this story also encompasses Apple’s dire straits in the 1990s, and the multiple strenuous efforts it made to reverse the decline and get back on its feet, both on hardware and software. This story is also about the roads not taken, the roads wrongly taken, and in the end, the road correctly taken and where that road eventually took Apple and Steve Jobs. So we are going to be covering a lot of ground here, and I am going to be going off on a lot of tangents as I try to tie everything together in the end.

I do promise to properly pronounce Mac OS X as Mac OS 10 this time, proving that I do actually pay attention to the feedback and constructive criticism that I receive, although I will of course probably mispronounce at least a word or two somewhere in this video.

So join me as we journey back to the early 1990s, and a flailing computer company that is rapidly hemorrhaging cash, led by a CEO whose vastly diminished personal wealth is shrinking ever more every day as he not only struggles to keep his imploding computer company afloat, but also fights to keep a completely separate company from going under.

Pixar was wrestling with the production of the first computer animated feature film and was having a brutally difficult time sorting out not only story issues that forced a temporary halt in production, and not only the teething problems that came with making a film on the cutting edge of technology, but also financial issues. Put simply, Jobs had two flailing companies making demands on him and what was left of his Apple-derived fortune.

Matters came to a head in 1993, not a very good year for Steve Jobs-although in fairness the previous eight years had also been pretty up and down.

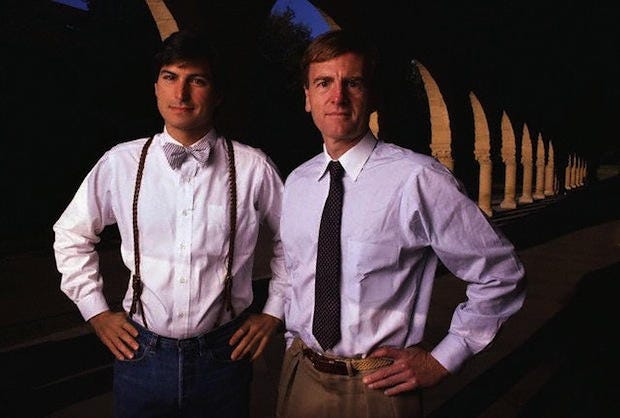

As a brief recap, in 1985 Jobs had attempted to regain control of Apple from the man he had personally hired to help run it, John Sculley. The coup attempt had failed and Jobs had been relegated to an honorary role that carried no authority or responsibilities. After going through the enormous turmoil and near emotional collapse that this had caused in himself, Jobs decided to start a new computer company that would create the next major computer family, running a cutting edge new operating system, whose success would validate to everyone that Apple had backed the wrong horse in Sculley.

After leaving Apple, Jobs had moved quickly to sever his remaining ties to the company he had co-founded. On March 15th, 1986, he completed selling off all but a single share of his Apple stock, which he had held onto so he could still receive Apple’s stockholder reports and appear at shareholder meetings, should he so choose. I also personally suspect that Jobs could not bring himself to completely cut all ties to the company that had been his life, and thus would always have found some excuse to retain this single share.

Jobs had started with 6.5 million shares, representing 11.3 percent of the total and making him Apple’s largest single shareholder. This massive selloff, that he had begun on July 22, 1985 by letting the SEC know that he planned to sell off a total of 100,00 shares, had been a rather pointed signal to the rest of the world that Apple’s former golden boy did not have any confidence in Apple’s continued longevity.

But this rather petty way of backhanding Apple had badly backfired, costing Jobs money that he badly needed by the 1990s. In spite of Apple’s struggles and the moribund state they had fallen into by the early 1990s, the stock was still considerably up from when Jobs had sold it, a fact that had cost him tens of millions of dollars. Specifics are hard to figure out exactly, but using Yahoo’s stock history, in 1985 it looks like Apple stock traded in an adjusted range from 9 to 13 cents or so and in 1993 ranged from 20 to 53 cents, meaning that even in the worst case scenario, he could have doubled his money, and best case, quadrupled it since Apple had also done a two for one stock split in 1987.

Note that this is the adjusted price based on the current amount of Apple stock and normalized for stock splits and adjustments since then. So the actual specific price was considerably higher back then, with the unadjusted prices in 1985 ranging from 29.01 in January to 22.00 in December. In 1993, the stock price started the year at 59.51 in January and ended the year at 29.25.

Using the adjusted stock prices allows you to do a fairly direct comparison between Apple’s stock prices then and their stock prices now that would not otherwise be possible. In the words of an article I found that explained this, “Historical stock prices must be transformed so that the data is indicative of the total return that would have been achieved from holding a particular stock over a particular period of time. The transformation must create a series that reflects the dividends, mergers, spinoffs, splits and various other events that impact the stock’s total return.“

I’ll link to an article that tries to explain it better, as well as another one that shows Apple’s adjusted and non-adjusted historical stock prices. Using Apple’s adjusted stock price makes sense in the context of comparing 1985 and 1993, however when we start talking about potential Apple buy-out offers, I will be using the non-adjusted stock price. The reason for this is that if I used the adjusted price, discussing acquisition negotiations whose price was based around the then-current stock price of Apple won’t make sense.

Anyhow, Jobs' decision to dump his Apple stock in 1985 had cost him an enormous amount of money. His actions had cost him tens of millions of potential dollars (strictly viewed in the context of the early 1990s, 11.3 percent of Apple today would be worth umm…considerably more) which was money that he sorely needed as NeXT was badly floundering.

From the start, NeXT’s line of expensive computers had mostly been praised for their innovation, particularly in software, yet had found few buyers and little to no success. This was in spite of the powerful and advanced features that NeXT computers and the NextStep operating system offered to its users. Those that could afford one, or worked for a company that provided one to its employees, received the benefit of a fairly powerful system, albeit one with some poor design choices such as the infamous magneto-optical drive, paired with an operating system that was object oriented and years ahead of its time in any number of areas, especially including its advanced networking abilities.

The tiny install base of NeXT systems genuinely had an impact on the computing landscape vastly out of proportion to their minuscule market share. For example, the pioneering shooter Doom was programmed on a NeXT system, with ID Software finding its development tools so significantly superior to DOS based ones that they bought a number of NeXT machines for their developers, who put them to work creating both Doom II and Quake.

Even more consequently, the World Wide Web was also created on a sleek black NeXT machine. Tim Berners-Lee used his NeXT computer at CERN to not only create the first web browser, but also to create and run the world’s first web server that hosted the world’s first web address and the website located there. When the 2012 olympics were held in London, Tim Berners-Lee was part of the opening ceremony, sitting in front of a NeXT Cube.

Yet again, outside of these few high profile uses, few NeXT computers had been sold. The giant, fully automated factory that made the computers had built and sold fewer than fifty thousand machines since 1988. And fewer and fewer NeXT machines were being sold year by year, with even Apple’s shrinking numbers far outstripping NeXT’s. As Windows exploded in popularity and PCs flew off the shelves in ever-greater numbers, a superior operating system and good hardware specs only went so far.

NeXT computers were aimed at a target market that didn’t really seem to exist in any measurable size, well off consumers who wanted the polish and features of the NextStep operating system, running on a sleek modern computer, but who were also fine with a limited hardware selection, few applications, and an ecosystem that was incredibly limited.

The NextStep operating system was great if you were a programmer looking to take advantage of its excellent development tools, but if you just wanted to balance a checkbook and play some games…well you COULD do that on a NeXT computer…depending on if the games you wanted were one of the few available for the platform…but you could also do that on a much cheaper PC running Windows. Sure it wasn’t as easy to use, far from it…but it also was far less expensive and had an abundance of choices available in both hardware and software.

And while the boring beige consumer hardware of the early 1990s was a far cry from NeXT’s sleek looking computers, a PC owner could console himself with a massive and rapidly expanding hardware and software ecosystem that, for all of its faults, was commoditizing the personal computer in a way that had never been seen before. To reverse Jack Tramiel’s pithy saying, NeXT was creating computers for the classes, not the masses, and there wasn’t enough interest from the former to support a viable business.

NeXT was losing money hand over fist, losing investors willing to fund its extravagant operations, and Jobs was no longer among America’s wealthiest elite, his wealth far diminished from what it used to be. Forget parity with Bill Gates, Jobs had fallen so far that he was merely wealthy, not super wealthy, and he was starting to approach the limits of what his personal funds could do to sustain NeXT.

Jobs also was wrestling with more than just NeXT’s financial woes, as his 1986 purchase of Pixar from a mildly desperate George Lucas had also turned into a significant cash drain. Pixar had never been profitable, and its line of powerful computers and software, for all their brilliance, had sold in quantities that made NeXT’s anemic sales look like Compaq’s.

With the exception of providing Disney with a new computer based ink-and-paint system called CAPS, Pixar’s hardware and software efforts had been a failure by any metric one cared to use. And Pixar was still solely sustained by Jobs’ increasingly shallow pockets, the flashy and award winning animated shorts providing lots of positive press but no profits. Yes they were working on a brand new, fully 3D animated feature film called Toy Story, but in 1993 it was still deep in a troubled production and nobody knew yet how it would be received.

Although at least Disney was mostly financing Toy Story’s production, initially with a set budget of 17.5 million, with any costs beyond the budget being split between Pixar and Disney. Unsurprisingly, making the first full length CGI feature film turned out to be more expensive than anticipated, and Toy Story started to run over budget, rather considerably.

Pixar was so short of cash that Jobs was forced to personally guarantee their line of credit needed to cover their half of the budget overrun, which was at least three million dollars. This was yet another worry for Jobs, as both of his companies floundered. To reiterate, Pixar was in such serious financial straits that they couldn't come up with a three million dollar line of credit without Jobs cosigning for it.

Over at NeXT, key personnel kept vanishing, as people got disillusioned by the bitter reality of NeXT’s future prospects or lack thereof and chose to move on. Even more wanted to move on, but were unable to due to being tied to NeXT by loans the company had advanced them back when the future looked rosy. These loans had to be repaid immediately if the employee left NeXT, and thus a number of employees, despite their wishes, were chained to NeXT whether they liked it or not.

A tough decision had to be made if NeXT was to survive. Actually a lot of tough decisions had to be made. But the first and most immediate one was to massively slash expenditures and get rid of the biggest drain on NeXT’s capital…the sleek hardware.

As February 1993 started, InfoWorld’s Cate Corcoran got a scoop from a source inside of NeXT that claimed that NeXT was going to exit the hardware business entirely. Unwilling to go to press with this news purely on the basis of one possibly anonymous source, Cate took the tip to her editor.

This editor had already heard from someone who had unsuccessfully attempted to order a new NextStation, and had their order canceled. This made two confirmations, and a third was found when InfoWorld’s gossip columnist heard independent corroboration of NeXT’s exit from the hardware business from a disgruntled former NeXT executive. Three sources were enough for an article to be written, which ran in InfoWorld’s February 8th issue. In a sign of just how NeXT’s importance had fallen, the story wasn’t even the headline story in the issue, although it did make page 1.

The article is only a handful of paragraphs long, split between the start of the story on page 1 and the conclusion on page 75, but it does contain the basic elements of what was happening. The article does hedge its bets a bit however, saying that Next was considering selling the hardware business to another company, most likely Canon, or might start selling rebranded hardware manufactured by Canon with Next’s name simply slapped on. It also has a rather spicy quote from an analyst named Mark Cain who said “If they’re turning themselves into a software company, this is probably the first really smart business decision Jobs has ever made.”

The following day, February 9, 1993 was when ax officially fell, a day that became known as Black Tuesday. Canon took over NeXT’s sleek and mostly unused factory(although they would later back out of the deal), and according to George Cummings, one of NeXT’s executives, seventy percent of NeXT’s employees were let go, which would be about 371 employees.

I’m not sure if this figure is accurate however, as another source, Apple Confidential 2.0, says that 280 out of 530 total employees were let go, which would be a still massive layoff of fifty-two percent. Yet another source, The Second Coming of Steve Jobs says that 330 out of 530 people were laid off, which works out to about sixty-two percent. So I guess pick whichever number sounds most plausible to you, all of them point to a majority of Next’s staff being laid off.

More news organizations picked up the story after this, such as the San Jose Mercury News, who ran an article stating that NeXT would no longer be a hardware and software company, the hardware business being discontinued entirely. From henceforth, NeXT would focus on its NextStep operating system alone.

On February 10th the New York Times carried the news under the headline “NeXT To Sell Hardware Side and Focus On Its Software”, and after giving some details about how Canon had bought NeXT’s hardware division, proceeded to quote a healthy amount of Jobs’ masterful ability to spin bad news as good.

Jobs’ bland statement that "We understand we could work really hard for the next few years and emerge as a good second-tier hardware company. But people are telling us there are just three competitors for the software and we have a chance to be a first-tier software company", neatly disguised the fact that NeXT had completely failed to build a sustainable hardware business and there was little hope of that ever changing, no matter how many more years and how much more money was thrown at the problem.

The article ended by stating the genuine fact that “NextStep has emerged as the company's real strength. Because of its object-oriented programming, a modular approach to software design that makes it easier to re-use or modify large chunks of software code, NextStep is finding favor among medium and large organizations that must create custom applications in-house.”, although the fact that NextStep made it much easier to build complex applications did not mean for a minute that there was an underground yet massive industry of NeXT using software developers.

Getting set up with a full NeXT development environment had always been expensive, and given that Microsoft practically gave away Windows development tools…tools that ran without issue on the PCs the majority of computer users owned…well something usable that you can afford typically beats something neat that you cannot.

Interestingly, according to several comments left under my first video, either just prior to shutting down or shortly after shutting down the factory made a special run to quietly produce at least a few thousand more NeXT computers. These computers were destined for the National Reconnaissance Office, who according to one comment, was NeXT’s largest single customer. According to another comment, the factory was run for a week straight, with the goal of producing a five year supply of computers and spare parts for multiple government agencies’ usage.

NeXT Computer was then renamed to NeXT Software, but continued to just be referred to as “Next Inc” in trade publications and such, same as it was prior to closing down the hardware side of things. And the oddball styling of the name “NeXTStep” was also changed to a more conventional “NextStep.”

Steve Jobs moved quickly to try to keep the lights on, releasing the first version of the NextStep operating system for Intel based machines just a few months after Black Tuesday. This version, formally called “NextStep, Release 3.1” was released on May 25th, 1993, at the NeXTWorld Expo in San Francisco. The crowd was enthusiastic, but a definite minority compared to something like Comdex, with InfoWorld citing two thousand conference attendees and eight thousand exposition attendees in total.

Those two thousand attendees were there for Steve Jobs’ keynote speech, and InfoWorld’s publisher Bob Metcalfe (yes, that Bob Metcalfe, the one who invented Ethernet) said that all the attendees were “excited”, although he also dryly commented that “Several Next enthusiasts told me that 20 percent of NextStep’s installed base attended NextWorld Expo; I suppose this proved their commitments. To be sure, nowhere near this percentage of Windows users attended Windows World at Comdex.”

According to Jobs’ keynote, forty thousand copies of NextStep had already been ordered, and Next was anticipating sales of 100,000 copies of NextStep the following year, 1994. But man, if you wanted to get NextStep for your 486, you had to be prepared to pony up some big bucks as the standard install of NextStep OS 3.1 would run you 795 dollars, and a developer version would be more than double that, at 1995 dollars. Now, I am reading this information from an ad I found from Next, that ran in InfoWorld’s June 14th, 1993 edition.

This ad offers a special deal of 299 dollars for both the developer and the user versions of NextStep OS, but seems to suggest that that developer version was normally 795 dollars and the user one was 1995 dollars instead of the other way around. Everything else I see about NextStep OS’s pricing says 795 dollars, so my assumption is that the ad has the normal prices backwards. Feel free to correct me in the comments if you know otherwise.

Even at 299 dollars, getting your PC into the Wonderful World of Next was expensive. Let's take a quick look at the pricing for competing 32 bit operating systems being sold in 1993, this chart being drawn from InfoWorld’s November 22nd, 1993 edition. By this point, NextStep OS had moved from version 3.1 to version 3.2, and its list price of 795 dollars, while not the highest, was definitely one of the highest. OS/2 2.1 was tied with Novell Unixware at 249 dollars, then came Windows NT at 495 dollars, and then NextStep and Solaris 2.1 were tied at 795 dollars. The only operating system more expensive than NextStep was something called SCO Open Desktop, a Unix distro that I know absolutely nothing about.

So NextStep’s pricing put it well out of consumer territory, and up against the heavy hitters of Windows NT 3.1 and OS/2 2.1. Now OS/2 2.1 was not exactly selling in numbers that were scaring Microsoft, but its install base dwarfed NextStep, and since it only cost a third the list price…and could natively run pretty much every Windows 3.1 application apart from ones that used Windows Enhanced mode…this pricing seems extremely foolish. Even at the 299 dollar promo price that the ad from five months previous had offered, NextStep was still more expensive than OS/2.

Obviously Jobs was leaning really hard into NextStep as being the ultimate developer system, claiming at the 1993 NextWorld Expo that developers using NextStep can speed up their development time literally ten fold. While Bob Metcalfe was moderating a panel called “The OS Wars” at the same NextWorld Expo, he asked one of the panelists, Mike Adelson, if he had observed Jobs’ claimed ten fold improvement in development time.

Adelson responded that while he had not observed a tenfold improvement yet, he had seen a fivefold speed increase. That was quite impressive, if not quite at the level Jobs was claiming, but was that really a feature that would cause enough people to purchase NextStep to make it a viable business?

I also want to call out one more thing from the ad, as it contains the tagline “the object is the advantage,” a phrase that I feel is not exactly inspired ad copy, although it arguably ranks ahead of every OS/2 Warp related tagline, or at least it did once IBM was forced to drop any Star Trek adjacent marketing and only use the alternative meanings of “warp”, such as the psychedelic ones.

1994 was NeXT’s first full year as a software only company, with their primary focus being the Intel version of NextStep, which was sold as bringing the benefits of the NextStep operating system to the Intel based PCs that dominated the personal computer market. Remember that NextStep had originally been developed for the same Motorola 68k processors that Apple was in the middle of the painful process of transitioning away from, switching to the powerful new PowerPC chips. Porting NextStep to be able to run on Intel based systems would allow it to reach a much broader market, and version 3.1 had been the first one available for Intel.

And while the NeXT’s base of fervent users continued to be as devoted as ever, 1994 just didn’t see much progress on the sales front. Byte magazine covered the then current-state of NextStep in its November 1994 issue, in a two page article titled “Whither NextStep?”. In this article it is pointed out that although NextStep was “arguably the most influential operating system of the last five years: widely envied, often imitated, seldom matched”, it still lacked “a significant number of users. After five years of sales, the total number of active NextStep seats–systems art which you can sit down today and use NextStep–is less than the number of new Mac systems sold each month or the number of new Windows systems sold each week.”

And that 795 dollars price tag was still being stuck to, which was undoubtedly yet another huge drag on adoption. The article does end with a prescient quote, “Even if NextStep does decline, its legacy and influence will be felt for years to come, but that may be small comfort to those who have poured their lives into it.”

The final clause in the quote undoubtedly was deeply personal to the author of the article, Bruce Webster, who was then the chief technical officer for a company named Pages Software, a company developing NextStep applications.

InfoWorld covered the release of the next version of NextStep, version 3.3 in the January 30, 1995 edition, written by the only NextStep user at InfoWorld, Laura Wonnacott. She praised NextStep 3.3 as an excellent upgrade, and also touched on the fact that NextStep 3.3 now came with a 30 day trial of SoftPC, a Next application from Insignia Solutions that enabled a virtualized version of MS-DOS and Windows to run. SoftPC wasn’t a Next only developer, I actually remember using SoftWindows 98 on the family Mac back in the early 2000s.

And it was not a good experience, although since I was only interested in playing games on it, it wasn’t really a fair test of it. Still, its inclusion in every NextStep 3.3 install, even if only as a 30 day demo, shows that Next was at least trying to get more consumers interested in switching to NextStep.

Of course, to buy NextStep 3.3 still costs a whopping 799 dollars, or 1,662 dollars in 2024 dollars. Even upgrading was a still painful 199 dollars, or 413 dollars in 2024 dollars, so once again, I doubt NextStep 3.3 moved the needle too much on people’s interest. People talk about the Apple tax today, but the NextStep tax was quite a bit worse.

Toy Story’s Explosive Success

Properly covering Pixar’s road to Toy Story would require its own dedicated video, but it obviously deserves to be mentioned again here, as Toy Story’s release in 1995 not only literally changed the movie industry, but its success gave Steve Jobs a massive infusion of cash, filling his personal coffers to overflowing. Toy Story’s influence on the animated movie industry was not necessarily always for the better in my totally unsolicited opinion, as the magnificent 2D animation of Disney’s Renaissance movies, animation that Pixar’s CAPS system was an integral part of, still looks just as amazing today as it did thirty years ago. Meanwhile the early 3D animation that Toy Story utilized…well…at least the story is just as good today as it was back then.

Not that it's relevant to this video, but I miss the classic 2D feature film animation that reached its peak in the 1990s. Also, The Emperor's New Groove is the best animated movie Disney ever made, beating out every other animated movie from the Disney Renaissance. Yes, that’s what I said, and if you disagree with me well…you are undoubtedly an intelligent person with an informed opinion…that just so happens to be wrong.

Ahem, now where was I…oh yes back with Toy Story, whose massively successful release drove Pixar all the way to its IPO in November of 1995, which managed to do what Apple and NeXT couldn’t…make Steve Jobs a billionaire and restore him to the financial security and net-worth that he hadn’t seen in, well technically ever.

WebObjects and OpenStep

One of the first tangible products to emerge from Next’s new, post-hardware existence was WebObjects, which was a way of bringing some interactivity to the still very rough around the edges World Wide Web. Remember, the Web as originally developed was not interactive, rather websites were collections of static pages of content, really more like accessing and reading articles.

To move beyond that would require developing ways of not only making content dynamic, but also allowing for dynamic websites. And what do I mean by that? Well, in the words of a September 30th, 1996 InfoWorld review of WebObjects, “If World Wide Web technology is to grow beyond its current role as a way to publish mostly static documents, it will have to work around two shortcomings: its stateless nature and its incapability to query, retrieve information from, and update enterprise-class databases in real time.”

WebObjects initially ran on a wide variety of operating systems, ranging from Windows NT, to Solaris, HP-UX, and unsurprisingly NextStep itself. The latter of course making it easier to eventually port WebObjects to Mac OS X several years later. All web browsers of the time could allegedly use it, although I do wonder if it had any special options that Netscape Navigator could make use of, given that it was the reigning browser heavyweight of that early World Wide Web era.

WebObjects was not cheap, even by the standards of the time. According to InfoWorld, each developer using it required their own 3,000 dollar license and the server part of it also ran 3k per processor. But wait, there’s more. That pricing was only for WebObjects Pro, there was also WebObjects Enterprise, which cost 5k per developer seat and 25k per server processor. I don’t actually know what the difference was between the two versions, InfoWorld’s review focuses on the Enterprise version, and simply says that the Pro version is “less-full-featured”.

Also let’s all take a minute to appreciate the phrase “less-full-featured”, which for some reason, possibly because as I type this it's currently well past midnight and I’m tired, as a rather roundabout way of saying that the Pro version lacked a number of features found in the Enterprise version.

Whether WebObjects’ steep pricing was due to Next’s dire financial straits, or the result of Steve Jobs’ lack of interest in undercutting the competition on price, I leave up to you to decide.

Then there was OpenStep. Announced in November of 1993, as part of a partnership with SunSoft that also saw them invest 10 million dollars into Next, OpenStep was lauded by NextWORLD magazine who attempted to explain exactly what it was supposed to be, saying it was a subset of the existing APIs in NextStep 3.2. Although details are still being worked out, the specification is expected to include all portions of NextStep that are independent of the operating system, including AppKit, DBKit, Display PostScript, distributed objects, and ObjectiveC.

Basically OpenStep was to be a collection of the NextStepOS APIs that could be split off from NextStep itself, and run independently. And why would anyone want to do this? So far as I can tell, the goal was to take what made NextStep such a powerful development tool for building applications, and make them platform agnostic. It wasn’t just Sun’s powerful workstations running Solaris that would be able to make use of OpenStep, it would also eventually be available for Windows NT as well.

So what exactly is the difference between OpenStep and NextStep? It seems that NextStep is an operating system, and OpenStep is a collection of NextStep’s API’s bundled together into a graphical environment that runs under other operating systems. However this naming is very confusing, and I even found an almost thirty year old thread where someone asked what the differences were between the two, and in one of the responses, the phrase “clear as mud” was used.

Another source, the awesome website toastytech says that “NextStep was the operating system created for the NeXT computer (a Motorola 68K based machine), and later ported to to the Intel x86/PC platform when NeXT shifted focus from being a hardware company to a software company. OPENSTEP is the descendant of NextStep, although technically "OPENSTEP" refers to a set of portable APIs based on those of NextStep that NeXT made available on Mach (The Unix-ish core that NextStep ran on), Windows NT, and Solaris.”

So there you go, NextStep is the operating system and OpenStep is a collection of APIs that functions as a GUI that can run on top of Mach, NT, and Solaris. This is absolutely not confusing at all to anybody ever and everybody including me who discusses this story always gets the terms exactly right.

Apple’s Dire Straits

As Next struggled to make it as a software only company, and Pixar rocketed off to overwhelming success off of the back of Toy Story, how was Apple doing?

Well, by the mid-1990s, Apple was in dire straits, struggling on all fronts, and with its glory days seemingly long behind it. The Macintosh operating system, although still considered a great user experience, and one that Windows still fell short of matching, was aging poorly. Originally designed for the single tasking days of the original Macintosh and its Motorola 68k processor, it had serious architectural problems that were increasingly causing issues. These included cooperative instead of preemptive multitasking and poor memory management.

Yes Windows was still an inferior user experience overall, I’m sure some will disagree with me in the comments, but this is my position and I’m sticking to it…but Windows’s own creaky MS-DOS underpinnings were getting better and better hidden and Windows 95 had some significant architectural advantages over the aging Macintosh operating system. Plus of course there was Windows NT, which was gaining in maturity and would be the basis for mainline consumer Windows in just a few years.

These problems were not news to Apple, and for years they had been struggling to come up with a way to transition away from the poorly aging classic Mac operating system, to a new and improved one that would still run most legacy Mac applications but would resolve the issues that were holding the Macintosh back. Every single attempt had failed, and while I am not going to get into the weeds too much on this, it's important to hit the high points of previous attempts to replace the Mac operating system as these failures provide a tremendous amount of insight into why Apple eventually made the choices they did.

It also gives some nuance to what was going on, and the fact that there really were no bad guys at Apple at this point, so far as I can tell everybody was genuinely doing what they felt was best for the company. The problem was that the company had simply become too chaotic and undisciplined over the past decade, and even though there was a massive amount of money being thrown around in all these various projects, the cohesive vision required to bring it all together and get everyone marching in the right direction…or even the same direction, well it wasn’t there.

And it certainly wasn't for lack of trying out new leadership and new ideas in the years since Steve Jobs had fallen from power. By the mid 1990s, Apple was a company in turmoil, having burned through multiple CEOs, none of whom proved able to grab ahold of Apple’s unique culture and get everyone moving in the same direction, with purpose.

John Sculley

John Sculley was the longest serving Apple CEO until Jobs returned, spending ten years at Apple’s helm. From 1983 to 1993 his tenure covered some major highs and lows for Apple, and is one that is difficult to reduce to a single judgment as to success or failure. While I don’t feel that Sculley really understood the Apple magic so to speak, he was a competent businessman who made a number of right calls, and it was under his leadership that new Macintosh models started to come out that really started to realize the potential of the original, but sadly crippled Macintosh.

For all this Sculley bears a great deal of responsibility for the essentially rudderless state Apple found itself in by the early 90s, as its share of the personal computer market fell from twenty percent down to a mere eight percent.

It was also under Sculley that the first significant attempt to overhaul the MacOS kicked off in March of 1988. This was the infamous “Pink” project, started by five of Apple’s top software engineers, who convinced their managers to let them leave their respective divisions and work together on designing a new operating system. In the March 1988 meeting, they used pink, red, and blue index cards to write down the various features that the next generation MacOS needed.

On the pink cards that gave the project its name were written down the major features that needed to be in the new MacOS, such as memory protection and preemptive multitasking. The red cards had major advanced features written down, more of a wishlist than practical, features such as using voice commands to control the computer. Given the speed of personal computers in 1988, speech recognition seemed like a tall order and something best left to future releases of the next generation MacOS.

Lastly were the blue cards, on which were written features that could be incorporated into the current MacOS to help keep it competitive. The Pink project promptly ballooned into a massive behemoth that successfully vacuumed up enormous amounts of time, resources, engineers, and focus without really producing much of direct use.

The aging MacOS soldiered on, struggling in the face of Windows’ increasing dominance, with its proliferation all but guaranteed by the massive amounts of clone machines that were also hammering Apple’s erstwhile foe, IBM, harder by the day.

The only concrete thing to come out of Pink was, amusingly, the next major release of the MacOS, System 7, which came out in 1991. System 7 was the product of the Blue project, which was mostly overlooked at Apple as Pink was considered the future, and it was where everybody was pulling strings to get assigned to. In spite of being somewhat of a lower priority, System 7 was a solid upgrade to the MacOS and restored some of its competitiveness against its main competition, Windows 3.0.

During this time, Apple also spent heavily on the Newton project, and Sculley created probably his most enduring legacy by coining the name for the new category of device that the Newton was to represent. This was the name that would become the generic name for a whole class of handhelds, Personal Digital Assistants, or PDAs.

Yet the Newton, for all its revolutionary ideas, was an expensive boondoggle that burned up hundreds of millions of dollars over the years as Apple’s engineers and developers struggled to translate the revolutionary ideas embodied in Apple’s Knowledge Navigator concept into something far more modest that could be accomplished with the technology of the day.

Sculley also started dabbling in politics, and was involved in Bill Clinton’s original run for president. Between the time and money he was lavishing on the troubled Newton project, and the time he was spending helping the Clinton campaign, Apple’s board began to feel that his attention was not exactly where it should be.

Sculley was also apparently considering leaving Apple to become IBM’s CEO, which may not be one of the great “what-ifs” of tech history, but is still an interesting “what-if” nonetheless. He undoubtedly wouldn’t have messed up OS/2 any worse than IBM did without him, and there is at least a slim chance that he might have handled it quite a bit better. Granted that is a mighty low bar to clear.

Matters came to a head when Apple was facing having to report its largest loss of any fiscal quarter to date. The board had had enough, and in 1993 Sculley was forced out and replaced by the former head of Apple Europe, Michael Spindler.

Michael Spindler

Michael Spindler had started his career with Apple in September of 1980, overseeing Apple’s European marketing. Almost a decade later in January of 1990, he moved to Cupertino to become Apple’s chief operating officer, and then became Apple’s CEO on June 18th, 1993.

Spindler was a hard working guy who shunned the spotlight and mostly preferred to keep his head down and work. Rather memorably, one former Apple executive described Spindler as a man who “did not get to where he is by showing his butt in public.”

He guarded his privacy well, and kept such a low profile that he is easily overlooked in comparison with other Apple CEOs, who all enjoyed being in the spotlight to a greater or lesser degree, Steve Jobs of course being the most prominent of these.

Since Spindler took over as CEO in 1993, let’s take a look at the glorious chaos that was Apple’s 1993 hardware lineup, because it's a great example of the mess that Sculley had allowed the hardware side to degenerate into.

In theory the Quadra systems were the high end Macintoshes, big boxes with multiple NuBus slots that could be crammed full of expansion cards, held multiple SCSI hard drives, and could be specced out with eye watering amounts of RAM. These systems were aimed at professionals who needed the most powerful Macintosh systems available and had plenty of money to spend.

Then there were the Performa systems. These were aimed at the consumer markets, and sometimes came in integrated all-in-one designs so literally all you had to do was plug in the power cord, plug in the ADB keyboard and the ADB mouse to the keyboard’s built in ADB port and you were off to the races. However, Apple’s way of doing the Performa was itself rife with confusing decisions. An excellent look at the Performa line comes from MacWorld’s November 1992 issue, which has a full overview of the initial Performa systems and what Apple’s plans were for them.

Essentially, Apple wanted a new product line to sell through retail stores such as Sears. Part of the plan was to take existing, proven systems and rebadge them as Performas. So the LC II became the Performa 400 and the Mac Classic II became the Performa 200, the only original Performa with a built-in screen. Apple then created a new design, the Performa 600 and the original Performa trio was born. Two retreads and one new design.

Add some peripherals…hopefully I pronounced that right…and a mildly customized version of Mac OS System 7 that umm…well I’ll let the article explain it: For a start, the default desktop patterns appear in color on the 400 and 600 instead of a more staid gray pattern. After booting, a new Launcher utility appears in the bottom-left corner of the screen. It contains large, color application icons that require only one click to open; research with computer neophytes indicates that a double-click is too much for too many. All factory-installed applications are automatically available from the Launcher. Yep, single clicking to open an application was apparently a selling point, or so Apple hoped.

The Performas’ customized System 7 also shipped with an extension called At Ease, which went even further to make the MacOS look…well I’m not sure what a nice way to put it is. Let’s call it aggressively user friendly. Enabling At Ease meant that the trash can disappeared and the entire desktop was taken up by two giant single-clickable icons, one for Applications and one for Documents.

We had a Performa when I was a kid, and it was one of the all-in-one designs with both CD and floppy drives. Very solid computer that let me play Warcraft II well and Starcraft 1 at…tolerable frame rates. I was sadly disappointed some years later however, when I tried to get Warcraft III to run on it. Warcraft III: The Slideshow was not nearly as cool as Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos.

I might have some vague memories of At Ease, I’m not sure exactly what it was but I do remember stumbling onto something that made folders and applications into large buttons that launched with only a single click. Whether that was At Ease or something else, I do not know.

I still have the Performa hard drive…somewhere…but sadly the Performa itself eventually succumbed to a number of years of being stored in an unheated, uninsulated area. And since I live in a part of the country that can get down quite far below zero in the winter while still reaching triple digits in the summer, it didn’t survive. I tried turning it on about ten years ago and it flickered, gave a loud pop, and I smelled smoke. And that was the end of that.

The Performas were going to be sold in retail stores yes, but Apple was going to keep selling its other systems through its other channels. And since some of those systems were the same ones that Apple was rebadging and repackaging into Performas…you can see how it was getting confusing.

Anyhow, the next major product group was the LC systems, the LC standing for “low cost”. These Macs were targeted at the education market and entry level users. I have an LC II and an LC III, and they are fairly solid systems, just very limited.

So that’s the product matrix then right? Quadras for the high end, Performas for the mid-range, and LCs for the entry level? Seems fairly simple and not that far off from the famous four part matrix of systems that Apple moved to in the late 90s for reasons that we haven’t gotten to yet.

Well, in a sane world it would have been these three systems for desktop users, plus a wide range of PowerBooks to handle people’s portable needs. But oh boy was Apple’s product line-up far from sane, and there is no better year to look at to illustrate this than 1993. Pulling up the relevant page on the amazing EveryMac.com, we are presented with a formidable list.

In 1993 you could choose from the following Macintosh desktops and models that were released in 1993, this list by the way does not include previous models that may still have been available through various sales channels…these are just the models that Apple introduced in 1993 across its various regions, some of which were only available in certain regions. So let’s run through this amazingly long list Macintosh Color Classic, Macintosh Color Classic II, Macintosh LC III, Macintosh LC III+, Macintosh LC 475, Macintosh LC 520, Macintosh Performa 250, Macintosh Performa 275, Macintosh Performa 405, Macintosh Performa 410, Macintosh Performa 430, Macintosh Performa 450, Macintosh Performa 460, Macintosh Performa 466, Macintosh Performa 467, Macintosh Performa 475, Macintosh Performa 476, Macintosh Performa 520, Macintosh Performa 550, Macintosh Centris 610, Macintosh Centris 650, Macintosh Centris 660AV, Macintosh Quadra 605, Macintosh Quadra 610 (PC), Macintosh Quadra 650, Macintosh Quadra 660AV, Macintosh Quadra 800, Macintosh Quadra 840AV, Macintosh WGS 60, Macintosh WGS 80, and the Macintosh WGS 95.

An astounding thirty-one different desktop systems, across six different product lines, sold across three main channels: retail, education, and dealer. Plus the additional configuration options in RAM and installed expansion cards that you could potentially get, depending on where you bought the system from.

And what’s the difference between say a 25 mhz Centris 650 and a 25 mhz Quadra 605? Well they are both tower configurations…albeit one is a thick form factor and the other one uses the thinner pizza box style form factor. But the skinnier pizza box is actually the Quadra, which was usually the powerful system. And in this case, the Quadra has only one expansion slot, a PDS one. The Centris actually has four, three NuBus and one PDS.

It’s also interesting to see how many systems Apple released the previous year, 1992. That year saw a total of seven desktop models released, across only four product lines. So in one year, Apple’s desktop offerings jumped from seven systems and four product lines to thirty-one systems and six product lines. And on top of the massive confusion that such a bewildering diversity of hardware options created, there were also confusing pricing decisions creating consumer uncertainty.

And it's not like all of this confusion is only evident in hindsight, it was very evident at the time, with Macworld commenting on it in its October 1993 issue. The article, titled Securing Apple’s Future has a whole section on Apple’s bafflingly complex hardware lineup, saying “For quite a while Apple has been creating too many models that overlap each other in their price/performance. The combination of price cutting and the plethora of new systems has confused everyone who is trying to figure out what the best model is for a particular use. Many Mac buyers suddenly became gun-shy after the debacle of the IIvx, which within a few months of its introduction dropped in price by 35 percent and appeared to be superseded by the Centris machines. No one wants to buy a product that may be outdated only a few months after it debuts.”

Because yeah, Apple was also making bewildering pricing decisions that created even more market uncertainty, on top of its baffling product matrix.

Coming into the job as CEO, Spindler was convinced that Apple needed to merge with a larger company in order to survive. Now this wasn’t a new idea at Apple, nor was it a new idea to Spindler as while he was Apple’s COO, he had been involved with discussing a potential merger with Sun Microsystems in 1990.

This deal was apparently really close to happening, however it would have resulted in Spindler losing his COO position, since a successful merger would have seen Sun CEO Scott McNealy take over as Apple’s COO. It seems that Spindler was looking to avoid this, and thus jumped at the opportunity to back out of the deal that came when Apple decided to go into partnership with IBM on the ill-fated Taligent project.

The next merger possibility came in 1992, when Apple was in talks to merge with Eastman Kodak…and then that fell apart. Then a merger with AT&T was on the drawing board until talks fell apart in April of 1993, when AT&T decided to spend 11.5 billion dollars to buy McCaw Cellular Communications instead.

So when Spindler took over as CEO in September of 1993, he had already been involved in some fashion with multiple merger discussions with other large companies. Hence it's not surprising that one of his goals was apparently to make Apple an attractive acquisition target. This required cutting costs significantly, returning the company to profitability, and growing Apple’s market share.

Spindler acted swiftly upon taking over, laying off 16 percent of Apple’s employees, or roughly 2500 people, as well as slashing R&D by over 100 million dollars a year. He also canceled a number of projects that had no clear rationale for existing or were many years away from actually producing something usable.

These efforts paid off with a year of growth, a doubling of the unadjusted stock price to over 40 dollars a share, and successfully managing Apple’s transition from Motorola’s aging 68k line of processors to the powerful new PowerPC processors that strange bedfellows Apple, IBM, and Mototorola had teamed up to create.

Granted the migration was fairly smooth from a consumer standpoint, as backwards compatibility with 68k applications was very good, however Apple had apparently neglected to create good PowerPC developer tools, something that could have caused serious problems as frustrated developers gave up on the Macintosh and just switched their efforts to Windows applications.

Fortunately a company called Metrowerks had created an excellent IDE in CodeWarrior, and it quickly became the primary IDE for developing Macintosh PowerPC applications, at least initially. And let's pause for a moment to think about just how mind-numbingly foolish it was for Apple to push out PowerPC systems without ensuring that there were development tools already available for developers to prepare PowerPC native applications prior to the PowerPC systems’ release.

Contrast this with Apple’s most recent platform transition, where a special version of the Mac Mini called an Developer Transition Kit that used Apple’s A12 chip was made available to developers months before the new M1 systems launched. These development systems had a beta version of Xcode 12 on them, ensuring that developers could immediately start working to port their applications over to Apple Silicon well before launch.

Contrastingly, Apple’s PowerPC transition would have been seriously hamstrung, potentially even crippled, if Metrowerks hadn't released CodeWarrior with its PowerPC compiler. Apple’s generally favored IDE and compiler from Symantec, didn’t finally ship their PowerPC compiler until almost a year had passed from the original PowerPC desktops’ release.

And when Symantec did finally release their updated C compiler, Symantec C++ 8.0, Macworld commented that while there was a lot to like about it and it had a lot of great features, it was important to remember that “Many industry observers agree that Metrowerks’ development of CodeWarrior essentially saved Apple despite little to no encouragement from the company.”

Anyhow, Apple’s successful platform transitions from PowerPC to Intel, and then from Intel to Apple Silicon, have their roots in Apple’s transition from the 68000 to PowerPC, which was more-or-less successfully done under Spindler, even if there were some significant mistakes that Apple was fortunately spared the consequences of.

Spindler also started licensing out the Macintosh operating system to clones, banking on them taking market share from Windows while Apple kept its existing market share, the end result being a considerable increase in the MacOS’s overall install base. This was not exactly going to happen, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

With some wind beneath his wings, and after the successful PowerPC launch had made Apple and IBM feel all warm and fuzzy about working together, the two companies started discussing a merger. In October of 1994 executives from both companies spent two weeks at the Summerfield Suites Hotel in San Francisco, trying to find a mutually agreeable price for IBM to acquire Apple. However the talks fell apart when Spindler demanded 60 dollars a share, and IBM was only willing to offer 40 dollars.

When that merger fell apart, Spindler then started talks with Canon, who you might remember had also invested heavily into NeXT, just a couple years earlier. Canon offered 54.50 a share, but Spindler decided to take that figure back to IBM and try to get them to top it. He failed, and talks with Canon went nowhere.

Spindler then extended feelers to at least Compaq, HP, Toshiba and Sony, none of whom were interested. Then a rash of major inventory problems, product problems, price wars, and the juggernaut of Windows 95 hammered into Apple, and the company really started flailing and losing money.

And given the fact that Spindler was at the helm when Windows 95 stormed onto the market, it's worth touching on the threat this posed to Apple. A threat that did not go unrecognized in the Apple world, with MacWorld actually reviewing a full beta of Windows 95 in the February 1995 issue under the article title of “The New Windows Threat.”

And they did not casually dismiss it, saying towards the start of the review that All in all, Windows 95 poses a serious challenge to the Macintosh. Its graphical interface is good–in some areas better than the Mac’s, in some equal, and in others not as good. But Windows is no longer a wannabe. For most people, Windows 95 will be as good as the Mac, though different, and that’s a fundamental problem Apple must face soon.”

As Windows 95 neared its release, the MacOS was still struggling to fully transition to PowerPC. Yes the transition to PowerPC from a consumer level was a huge success, and the fact that it could seamlessly run 68k application code as well as PowerPC code, ensured that legacy Macintosh applications ran fine on it. However, apart from the already discussed issues with getting proper PowerPC development tools sorted out, there is another lesser known issue that the MacOS was dealing with.

In 1995 the then-current MacOS was system 7.5, released in September of 1994 which still contained more 68k code than PowerPC code. And this, while not directly evident to the end user, imposed a significant performance penalty in multiple areas.

According to an April 1995 article in Macworld titled “Long Road to a Native OS”, system 7.5 was still overwhelmingly using 68k code, with only slight improvements over System 7.1.2, which had been the initial release of the MacOS for PowerPC systems back in March of 1994. And yes, the fact that Apple released MacOS 7.1.2 only to follow it up with MacOS 7.5 six months later is another example of the baffling product numbering that was endemic to this era.

The Macworld article also states that there was not only a significant performance penalty for running 68k code on PowerPC, there was also an additional performance penalty that kicked in when the MacOS had to frequently flip back and forth between emulating the 68k and running native PowerPC code. As a matter of fact, this penalty was severe enough that MacOS 7.5 actually took a step back in several areas and moved some parts of the operating system back to 68k code in order to speed it up.

Apparently much of the I/O portions of system 7.5 were 68k code, with the article saying that developers estimated that moving that I/O code into native PowerPC would give applications that made heavy use of I/O a speed boost of up to fifty percent.

This is mostly likely the reason why the Power Macintosh 9500/132, which boasted PCI slots instead of the older NuBus slots, was limited in how well it could actually use those new expansion slots. In October of 1995, Macworld reported that it was being told by some vendors that although the theoretical speed limit for PCI cards was 132 MBps, limitations of the MacOS were bottlenecking speeds to a maximum of only 45 MBps, meaning that the old 68k code was potentially imposing an astonishing 66 percent performance penalty.

Even the ever-upcoming Copland was still expected to contain significant amounts of 68k code, with Apple saying it would only comprise five percent of the code base, while other Apple developers Macworld interviewed said that it was more likely to be “far short of 95 percent but should still be more than 50 percent.”

Windows 95 was coming in fast, and the MacOS was still struggling to make the transition from 68k, with even the long heralded Copland STILL not expected to be fully free of the older code, the current MacOS bottlenecking PCI hardware expansion speeds, a file manager that still was in 68k code meaning that the MacOS still couldn’t do multithreading or command queuing. And no actual fix was in sight from a disorganized and flailing Apple, the only defense being made for the MacOS’s shortcomings was to just say it would all be fixed whenever Copland finally shipped.

Then the introduction of the first PowerPC based PowerBook gave Apple a kick in the pants from the hardware end of things. The PowerBook line of laptops had been one of Apple’s few unqualified successes in the past few years, really setting the standard for what a consumer laptop should be and look like. People loved them and when Apple introduced its new PowerPC desktops, people immediately started looking forward to the first PowerPC laptop, which Apple was developing under the codename Anvil. Which was a really fitting codename in light of just what a weight they would turn out to be.

Apple had just started shipping these PowerBooks, formally dubbed the PowerBook 5300 to its dealers. And I mean literally just started, as fortunately for Apple they had only shipped a thousand units total, primarily to retail stores that hadn’t sold them yet. Then two pre-production models caught fire while being charged. One was being used by one of Apple’s developers and another one was actually at the Singapore based factory that was manufacturing the new PowerBooks. The culprit was their lithium-ion batteries, which had apparently had a significant design flaw.

For this reason Apple was forced to swap out the 36 watt-hour lithium-ion batteries with 26 watt-hour nickel-metal-hydride batteries, an older battery technology used in the final 68000 based PowerBook model, the 190. In a mild bit of karma, the Sony factory that made these defective batteries later burned to the ground for unrelated reasons.

The significant decrease in battery life forced Apple to slash the 5300’s price by 100 dollars across all models, and obviously caused significant bad publicity. And it would another twenty-plus years before they could commiserate with Samsung, so it was understandably a pretty stressful time.

And then there were the other problems the 5300 line turned out to have…because at this point in Apple’s history, problems tended to come in multiples. In the words of Apple Confidential 2.0, “The plastic case was prone to cracking, the power plug was too thin and often snapped off, and the power supply didn’t produce sufficient current to run certain combinations of expansion-bay and PC Card accessories simultaneously. Also, the circuitry responsible for reducing power consumption during Sleep mode would shut down before completing its job, reducing the maximum nap from ten days to four. Some units locked up completely if the user pressed the Reset button and Power key together.”

Far from being a badly needed shot in the arm, the introduction of Apple’s first PowerPC laptop had been a complete fiasco. And Apple wisely admitted this, with Apple COO Marco Landi bluntly saying “We screwed up, clearly.” Granted, the PowerPC desktops were doing pretty well, and were a definite bright spot, apart from the fact that 1995’s Apple was just as bad with naming models as in previous years.

New merger talks with Philips and Sun began running concurrently with all of this excitement of new hardware, poorly thought out naming conventions, and a struggling MacOS, however Sun backed out after hearing of Apple’s upcoming 69 million dollar quarterly loss in Q4 of 1995 and then Philips’ board rejected the proposed merger in a closely fought battle that saw the proposal go down in flames by a single vote.

Oracle’s CEO Lawrence Ellison even considered combining forces with his close friend Steve Jobs and using their combined finances to engineer a hostile takeover of Apple, but decided to drop the idea…for now. Ellison was a billionaire and since Steve Jobs was flush with cash from Pixar, they definitely had the financing to make a strong play for Apple if they chose to.

Matters came to a head at a shareholder meeting in January 1996, where an exhausted Spindler faced a very hostile crowd. He announced that Apple would be cutting another 1300 employees and reducing the number of Macintosh models offered in an attempt to reduce consumer confusion over Apple’s dizzying array of confusingly named computers. He also promised that the clone licensing program, which was running well behind schedule, would be speeded up.

It was all over for Spindler though, as Apple’s shareholders were out for blood. The board fired him as CEO and removed him from Apple’s board of directors. Although he could take comfort in his 3.7 million dollars of severance pay, 50,000 dollars for moving expenses, 150,000 dollars to pay off his house, and two years of free health insurance.

His hastily announced replacement was the man who would inadvertently start the process of bringing Apple back to success…Gil Amelio.

Gil Amelio

Gil Amelio was brought onto Apple’s board in November of 1994, and just over a year later replaced Spindler, with his first day as CEO falling on February 5, 1996. Amelio had a reputation as a turnaround artist, built off of his time at National Semiconductor where he had led the company to a 3.5 billion dollar increase in value, with National Semiconductor’s stock price quadrupling over Amelio’s time as CEO.

Amelio started his time as CEO at a time when the confusion and disorganization at Apple was really reaching a crescendo. Although in fairness I will say that Apple’s product lineup in 1995 was marginally less confusing than 1993’s complete mess, even though 1995 had seen an astounding 39 desktop systems released. These systems were mostly Performas and Power Macintoshes though, together with a single LC, the 580.

And the model numbers now sometimes did a little bit of a better job of communicating where the system stood in relation to other systems in the same family. But only a little bit, as while it's easy to see that the major difference between a Power Macintosh 7200/75 and a Power Macintosh 7200/90 is a 75 megahertz processor versus a 90 megahertz processor, it's a bit harder to figure out the difference between a Performa 6218CD and a Performa 6220CD.

In the latter case, both Performas have a 75 megahertz processor and the same 1 GB hard drive. The difference between the two Performas actually comes down to the fact that the 6218CD shipped with a monitor and 16 megabytes of RAM while the 6220CD had a TV card as standard, but shipped out without a monitor and with only 8 megabytes of RAM. So yeah, while some model numbers were a little bit more clear to read, others were still extremely confusing and poorly thought out.

For example, in 1995 Apple released the second generation PowerPC desktops, the 9500, 7200, 7500, and 8500. In so doing they discontinued the Quadra 950, Quadra 630, Power Mac 8100, Power Mac 7100, and Power Mac 6100, while continuing to sell Performas as well as a couple LC models, the 640 and 630.

And we mustn't forget the real highlight of the still being sold models, the Performa 6100 DOS Compatible, a system that came with a PDS expansion card installed that contained a 66 mhz 486 and supported up to 32 MB of RAM.

Let’s also review a great quote, as the usually solid Macworld vainly tries to justify Apple’s still bonkers naming convention.

And I quote, “The names for Apple’s new Macs may seem a bit confusing–why, for example, is the 7500 faster than the 8100, when a bigger number in a model name usually means “better”? In Apple’s naming scheme, the first digit represents the series. In that scheme, a 9 means a big tower (like the Quadra 950, Power Mac 9500, or Workgroup Server 9150), and 8 means a minitower (like the 8100 and 8500), a 7 means a traditional desktop case (like the Power Mac 7100 or 7200), a 6 means a flatter desktop case (like the Power Mac 6100; earlier 6 models, like the Quadra 630 and Centris 650, are now part of the 7 series), and a 5 means an all-in-one design (like the Performa 5200.) Within a series, the larger the model’s number, the more features it has; a number following the model number, after a slash, indicates the CPU speed.”

I hope you got all of that because there will be a test on it later, and it is not open book.

The standard setting PowerBook line that had done so much to create the modern concept of a laptop, was selling well, but Apple was also struggling to balance supply with demand, as well as dealing with design problems, such as PowerBook 5300’s catching fire due to bad lithium-ion batteries.

In 1995 Apple had released a total of eight PowerBook models, across three PowerBook lines, but 5300 variations made up four of those models. And Apple’s poor naming struck again, as customers who didn’t mind the 5300’s reputation had to figure out if they wanted a 5300/100, a 5300c/100, a 5300cs/100, or a 5300ce/117. So at least Apple was just as bad with naming their laptops as they were their desktop systems.

Overall, the hardware side of Apple remained a mess, and that’s not even counting the lackluster marketing and a very poor match of inventory to demand. Really the only bright spot was that when Amelio took over in early 1996, Apple had managed to more-or-less successfully pull off its first hardware transition, moving from the 68000 to the PowerPC.

This transition, like the PowerPC to Intel transition a decade in the future, and the Intel to Apple Silicon series of processors twenty-five years later, were massive changes that required a great deal of work to pull off without breaking compatibility with the existing body of Macintosh software. Part of the reason why Apple was able to so successfully move to its own Apple Silicon line of processors, was because it had already done these types of migrations two times before, and each time it got better at it.

But even the first time, when the company really was in its darkest hour and it seemed like things only were spirling further and further out of control…Apple still managed to pull off this complicated transition successfully. As with many things, it's important to keep some perspective on what Apple was doing wrong, AND what Apple was doing right at this time.

Not that there wasn’t plenty more hardware stuff going wrong at Apple at the time, what with the Newton project still eating up cash and the Apple Pippin game console about to faceplant. Amelio states in his book On the Firing Line: My 500 Days at Apple, that keeping the Newton alive was costing Apple 60 million dollars a year. And the Newton would continue to flounder until it finally arguably somewhat found its footing with the MessagePad 2000 and the eMate…and then was canceled.

And I am having to sit on myself so hard right now in order to keep from diving down the Newton rabbit hole. Way back at the start of the channel in 2017, I actually wrote a 1500 word rough draft that covers the basics of the Newton’s fascinating story…and it's been sitting there for the past seven years, waiting for me to have the time to sit down and expand it out into a full documentary.

So let’s just say that when Amelio took over, the Newton was not exactly a bright spot in Apple’s lineup, it was just another money losing division that was still struggling to find the right balance of software and hardware that would enable it to finally get the Newton onto solid footing.

So Amelio took over a company with significant challenges in both hardware and software. However the greatest challenge was the software one, as there still was absolutely no clear plan in place to get a next generation MacOS finished and shipping.

Every single attempt to create a next-generation Apple operating system had failed, or was in the process of failing. When Amelio took over as CEO, the only thing of substance that had come out of any of Apple’s attempts to overhaul the MacOS was the now four years old Mac System 7 line, which had basically been a bandaid for the MacOS that didn’t do a whole lot to advance the operating system and didn’t fix the major architectural issues, but did slap a bunch of duct tape on the aging MacOS that allowed it to mostly be competitive against the competition.

For example, with System 7 the MacOS finally had a form of multitasking in the form of building the MultiFinder extension directly into the operating system, although it was cooperative rather than preemptive, couldn't really use virtual memory apart without the help of a third party utility from Connectix called Virtual, and had a lot of idiosyncrasies.

Because it was a duct-tape solution for the MacOS’s native lack of multiprocessing, it didn’t play well with things such as Apple Unix implementation, A/UX, which, although it did let you simultaneously run Unix and Macintosh applications…doing this had the potential to basically collapse the MacOS back down to its single-tasking roots according to Byte magazine, who warned “that multiple tasks under MultiFinder will not run reliably in conjunction with A/UX. According to Apple’s product managers for A/UX, the Unix preemptive schedule can ‘bring down MultiFinder’”.

Now in fairness, this article was from 1990 when MultiFinder wasn’t directly incorporated into the MacOS, and wouldn’t be until System 7 released the following year, however I find it unlikely that MultiFinder’s behavior changed in this regard. Perhaps somebody in the comments can confirm, did running A/UX under MacOS 7 prevent you from running more than one Macintosh application concurrently?

The MacOS could also finally handle hard drives that were stuffed with lots of files and nested folders. But these and other improvements were simply bandaids, duct taped onto a system architecture that while it still provided a superior user experience to Windows, was increasingly creaky underneath. These issues were not really dealt with in future versions of MacOS 7, because they really couldn’t be.

By the time Amelio took over as CEO, the most recent release of the MacOS, system 7.5, had not materially fixed any of the MacOS’s issues. Because again, it wasn’t really possible to fix the existing MacOS, an entire rewrite was needed. Although system 7.5.2 was the first Macintosh operating system to carry the “Mac OS” title before the number, hence Mac OS 7.5.

Although I do feel like I should, after hammering on MacOS 7 the way I just did, spend a minute to give a bit of balance. I actually have quite a bit of experience with various flavors of MacOS 7, as that was what came with our family Performa back in the mid-1990s.

I liked the control strip System 7.5 added, and my first memories of getting onto the World Wide Web were made on that Performa, most likely still running some flavor of System 7, together with Netscape Navigator. System 7.5 included the necessary TCP/IP software to get onto the Internet out of the box, called MacTCP of course, although it was quickly replaced by OpenTransport, so I’m not sure which one I would have used.

As a kid I found system 7 easy to use, easy to play my games on (Reader Rabbit was and is awesome, as was Bolo, Armour Alley, Brickles, and many others including Wolfenstein 3D), and really didn’t generate too many problems requiring me to seek adult assistance. It was usually pretty stable right up until it wasn’t. Freezes were quite common when switching between applications, but if you only ran one thing at a time, I remember it being very stable.

MultiiFinder’s inclusion was definitely a bandaid and running multiple applications at once was really just asking for crashes. And in the classic MacOS, if an application crashes, but somehow doesn’t freeze the whole operating system, you still needed to reboot as fast as possible because you were then operating on borrowed time until a freeze hit

Apple’s software woes were not going away, there was only so much duct tape that could be applied, and the competition was getting fierce, especially in the aftermath of Windows 95 coming in like the proverbial wrecking ball on August 24th, 1995.

After all, what good was the powerful PowerPC hardware if the operating system running on it had serious issues that negated many of the hardware’s advantages? The aging MacOS, originally built to run a single application at a time, on a system with only 128k of RAM and no hard drive, was struggling mightily to keep up with the increasing demands made on it.

I do remember dealing with the classic MacOS’s tendency to, for example, crash when too many extensions were loaded. Or when switching from one application another. For example, I caused our G3 iMac to crash many times when I would use Command-M to switch Starcraft into windowed mode so I could bring up Netscape Navigator or Internet Explorer in order to look up a tutorial or a build order. Using AskJeeves to search of course. Every time I did it I would half wince, waiting to see if I was about to have to restart the computer. And this was under later versions of the classic MacOS, specifically 8.6 and 9.1. Problems such as this were even worse in the early-to-mid-1990s.

In 1995, when Amelio took over, the product line-up of new computers released that year was lengthy at 39 different desktop models, but was somewhat streamlined over previous years, with the model numbers making at least somewhat more sense than previous years. However the model lines were still rather confusing, with a new LC model, the LC 580, being launched as well as multiple new Performa, Power Macintosh, and PowerBook models. Plus a few new Workgroup Server, or WGS models.

But we must remember that these are just the new models launched in 1995, there were still Quadras being manufactured and sold for example, even though no new ones were launched. It was a mess, and really wouldn’t get fully sorted out until Steve Jobs forced everything to fit into a neat little four product matrix several years down the road. Well almost everything. Okay there were one or two outliers, but I happen to like the G4 Cube and wish I had one. There I go getting ahead of myself again, let's go back to 1995 and Amelio’s biggest challenge and headache, the problems with Classic MacOS operating system.

Flailing software

Apple’s operating system woes were of course hardly news to Apple itself, who again had been trying for years to come up with a viable way to bring the venerable MacOS into the modern era. We’ve covered the Pink project, a much lauded and interesting attempt to design the next generation MacOS, and one that staggered on for many years before finally collapsing.

Well it eventually sort of got folded into Taligent, the project trying to make a new MacOS that would run on not only the Macintosh but also IBM’s line of PowerPC based systems. Taligent needs a video devoted entirely to it, as does Pink to be honest. But the end result of all of this was nothing directly usable, and no actual progress made towards a new operating system. It had managed to burn through quite a lot of Apple’s money however.